Words in Light,Osawa Yuka Archives and Other News

On the Shelf

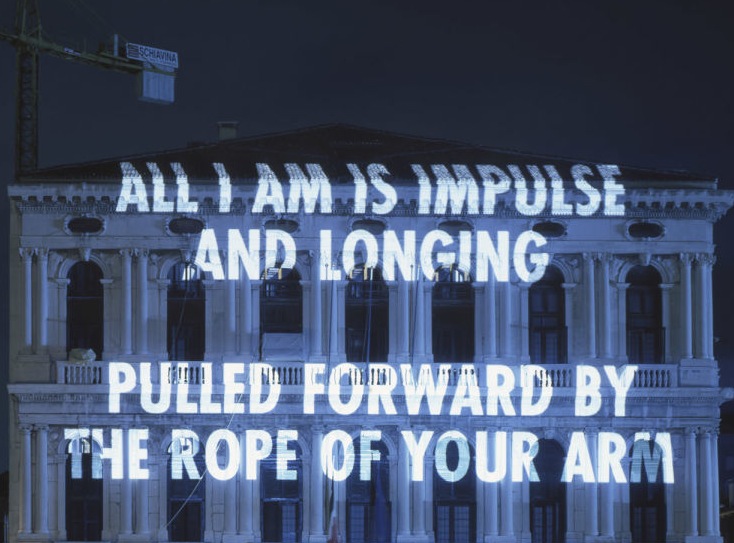

Jenny Holzer, Xenon for the Peggy Guggenheim(detail), featuring Henri Cole’s poem “Blur” projected on the Palazzo Corner della Ca’ Granda, Venice, Italy, 2003.

- Our advisory editor Hilton Als has an “emotional retrospective”—“One Man Show: Holly, Candy, Bobbie, and the Rest”—at the Artist’s Institute. Seph Rodney paid a visit: “The retrospective consists mainly of portraits, photographs found, taken, owned or commissioned by Als. He’s added colored light bulbs, placed next to the images to give the space a nightclub feel, with certain corners red and sultry, others yellow or blue, and some lime green. The institute’s town house with its hardwood floors, fireplace, and separate rooms is an apt place for this exhibition; the setting conveys a sense of intimacy with what are essentially Als’s ghosts. Walking the rooms you want to treat these unfamiliar memories—many of the characters depicted are only known to Als—with tenderness … The retrospective mirrors his critical writing: it’s deeply personal resonances refracted by his keen analytical attention so that intimate friends, historical moments, and his own self and experiences are progressively unpacked until the reader sees how they intersect and inform each other.”

- The artist Jenny Holzer has been projecting words onto buildings since 1991. Thus Henri Cole has seen several of his poems illuminated as “the touch of light against the surface of public spaces”: “Seeing my poems projected in this way, onto landscapes and buildings, I feel that the words leap out from a different zone, where they are observed as much as read. Language is more direct, open, unself-conscious, precise, and human. It doesn’t belong to me anymore but to the atmosphere, and this makes me happy. In Holzer’s installations, words—not images—strive to say something true, often about love, death, sex, war, or forgiveness.”

- Breaking: Hilary Mantel’s writing process reveals, emphatically, that this whole “novelist” thing is no mere pastime for her. “Some writers claim to extrude a book at an even rate like toothpaste from a tube, or to build a story like a wall, so many feet per day. They sit at their desk and knock off their word quota, then frisk into their leisured evening, preening themselves. This is so alien to me that it might be another trade entirely … The most frequent question writers are asked is some variant on, ‘Do you write every day, or do you just wait for inspiration to strike?’ I want to snarl, ‘Of course I write every day, what do you think I am, some kind of hobbyist?’ But I understand the question is really about the central mystery—what is inspiration? Eternal vigilance, in my opinion. Being on the watch for your material, day or night, asleep or awake.”

- An interview with Adonis, the Syrian poet in exile, finds him dismissing the idea that ISIScan write poems: “You cannot compare the bomb with the poem. You should not draw this comparison. Any ignorant bullet can change a regime, any despicable bullet can kill a great person, like Kennedy, for example. You cannot draw such a comparison because it is fundamentally wrong. Making poetry is like making air, like making perfume, like breathing. It cannot be measured by materialistic standards. This is why poetry despises war and is never related to it … poetry is a social phenomenon. When culture is a part of everyday life, everyone is a poet and everyone is a novelist. You now have thousands of novelists. But if you found five who are good to read, then you are in a good place. In America … there are thousands of novels; you will find five or six good ones, and the rest is garbage. The same goes for the Arabs. All Arabs are poets, but 95 percent of them are rubbish.”

- “The food of the true revolutionary,” Mao once said, “is the red pepper.” Which is great, unless you happen to be an aspiring revolutionary with a weak stomach. How, at any rate, did the pepper come to enlist itself as an agent of Maoism? “For years culinary detectives have been on the chili pepper’s trail, trying to figure out how a New World import became so firmly rooted in Sichuan, a landlocked province on the southwestern frontier of China … Food historians have pointed to the province’s hot and humid climate, the principles of Chinese medicine, the constraints of geography, and the exigencies of economics. Most recently neuropsychologists have uncovered a link between the chili pepper and risk-taking. The research is provocative because the Sichuan people have long been notorious for their rebellious spirit; some of the momentous events in modern Chinese political history can be traced back to Sichuan’s hot temper.”